"Jesus is the reason for the season goes" the saying, and getting to know Jesus is the purpose of this Lenten series - and Lent itself is a tool to remind us of Jesus, to reacquaint us with His story, to help us reconsider our lives - dare I say repent - and to choose to follow His path to the Cross.

There's a lot to Christianity, and a lot that people who are into Christianity argue about. And so I've been talking a lot of theology, philosophy, history, science and more; but all that can be overwhelming if you're unfamiliar with it - heck, it can be overwhelming if you ARE familiar with it.

So how can you get started with Christianity?

First off, Jesus saves if you believe in him; so learning about Jesus is a start on the right path. Next, find a Christian church whose creed speaks to you: this list is by church size, so the search [church near me] is likely to find one; I recommend you go to an [episcopal church near me] on the next available Sunday.

Why? Well, these are the first three theological steps on the road to becoming a Christian. First is awareness: you need to know about Jesus first. Second is belief: it's not enough just to know him, but to believe in him. And third is worship - but not just individually; communal worship, worship with others.

This is really important. Jesus didn't just preach on a mountaintop, though He certainly did that. He gathered apostles and sent out disciples who built communities. He once said "For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them," which is why many believe it's important to worship together.

If you're learning about Jesus, and you're gathering with others trying to learn about Jesus, then the Holy Spirit can guide you the right way. I recommend a church you're comfortable with to reduce distractions like disagreements over doctrine, but I also recommend a Christian church focused on Jesus.

"Look, Centaur, can you actually just tell me how to get started without opening my phone book?" "What, you guys still use phone books?" Oh, nevermind - if you want me to summarize, sure, hey, I can do that. I've already told you the three most important practical steps. Now, epistemological, or, what's up?

Surely you've felt at some point a presence larger than yourself, be it the simple recognition that the room or outdoor place that you're in is bigger than you are, or be it a deep internal experience, hard to quantify, of something to the world that's more than what you see and feel.

To Christians, this realization is the first step on the path to realize we exist in a Creation made by God. We don't mean this in the sense of a scientific explanation, as you have to take it on faith; but we do mean it as a fact: you live in a world where God has to exist, and is the only thing that has to exist.

God is the "ground of being," the logical foundation of existence, and everything else - including you - is something contingent upon God - something He created - a part of "Creation," which God designed to fulfill His purpose. So the fact is, if you want to do well in the world, you should be aligned with His will.

Now, we suck at that. Traditional Christians chalk this up to the Fall of Adam and Original Sin; I think it's a inevitable consequence of God wanting us to choose Him freely, given the limitations of finite agents acting as partially ordered Markov decision processes. But, tl;dr: we depart from his will. We sin.

Traditional Christians think God is infinitely good, and created an just universe; and in a just universe, sin needs to be punished - departing from God's will should have an inevitable consequence. But it sucks to blame limited finite creatures for failing to follow the perfect designs of an infinite unlimited God.

So it seems like God put Himself in a bind. Greek philosopher Epicurius argued if God is good then evil should not exist, but Christian theology inverts this: arguing about a mythical disembodied "evil" diverts attention from our personal role creating evil through sin, which logically a good God should punish.

Fortunately, God gave Himself an out: Jesus. God, in Christian theology, is one singular "being" existing out of and prior to time and space. But God exists, or is perceived by human beings to exist, in the form of three persons: Father, Son, Holy Ghost, sometimes said: Creator, Redeemer, Sanctifier.

In abstract terms, the Creator made the world, but it could not be made perfect just by a sterile act of creation. The Redeemer fixed the flaws of the world by acting in it to perfect it, and the Sanctifier continues to act in the world to bring people closer to the Creator through the Redeemer.

In concrete terms, God the Father may have made the universe and us, but either we screwed it up or free will requires it to be screwable. To un-screw it, God the Son came to Earth as a human being, providing an example and taking on our punishment, sending the God the Spirit to guide us after.

In religious terms, Jesus is both divine and human - He's the incarnation of God trying to fix the world and take responsibility for our punishments. Jesus not only provided us instructions on how to live in life, and a concrete example of how to live through His life, He took on our punishment on the Cross.

Theologians call this the "superabundant merits" of Jesus's unjust crucifixion: the extralegal, unjust, torturous execution of an innocent man who was actually on a mission from God was not just enough to wipe out the sins of the world, but to wipe out the sins of everyone for all time.

But in practical terms, it means Jesus, acting on behalf of - acting as - God, took on responsibility for the punishment that we might be owed for any sins we committed by not following His will, and further, took on the responsibility of showing us an example of a good life and teaching us how to live that life.

After Jesus returned to the Father, He sent the Holy Spirit - He sent another aspect of Himself - to help guide us. At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit woke up Jesus's apostles, turning them from scared followers hiding after the gruesome execution of their leader into bold preachers of His word, unafraid of death.

That transformation is available to all of us. Learn more about Jesus, attend worship at the Christian church of your choice, read a translation of the Bible you understand - I recommend the Oxford Annotated Bible and the Interlinear, but there's also The Message in contemporary language.

But the Bible is long. The short version is John 3:16: "For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life" and John 13:34: "I am giving a new commandment to you now—love each other just as much as I love you."

Pull on those threads, take a look at the Lord's Prayer, the Nicene Creed, and the Sermon on the Mount, and remember you must combine all three legs of the stool - Scripture, Tradition, and Reason, all of which have equal roles to play building our understanding - and you're well on your way.

Or, put another way, try to follow Jesus.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Allegedly, Epicurus.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

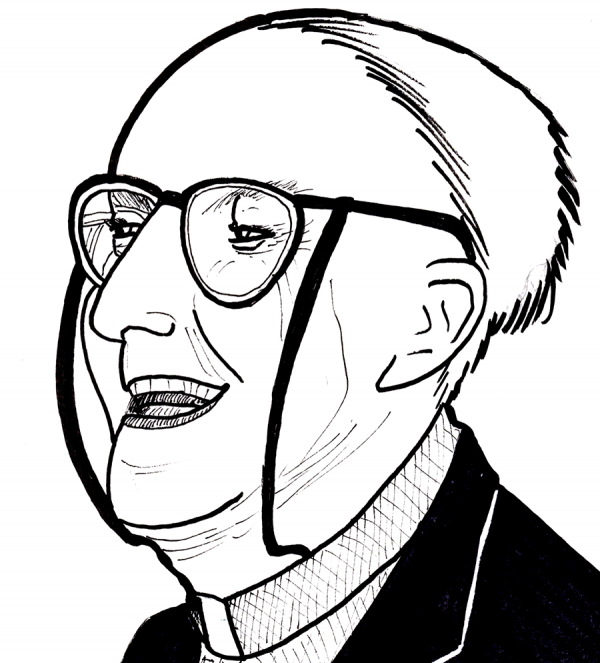

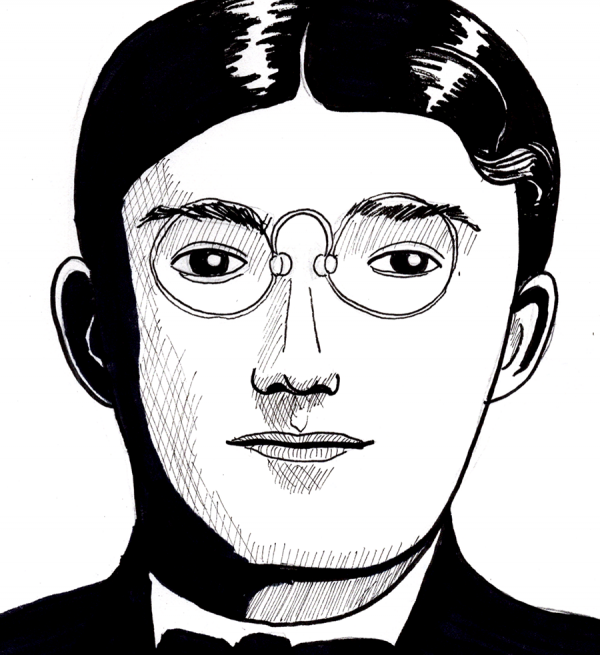

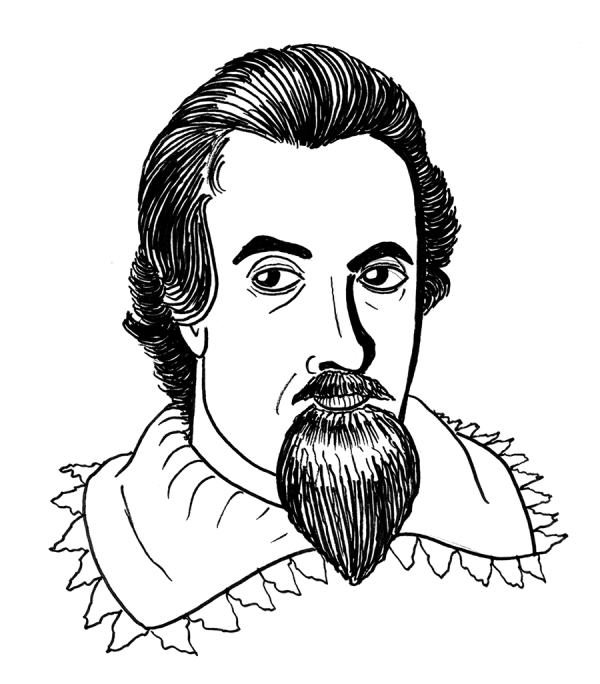

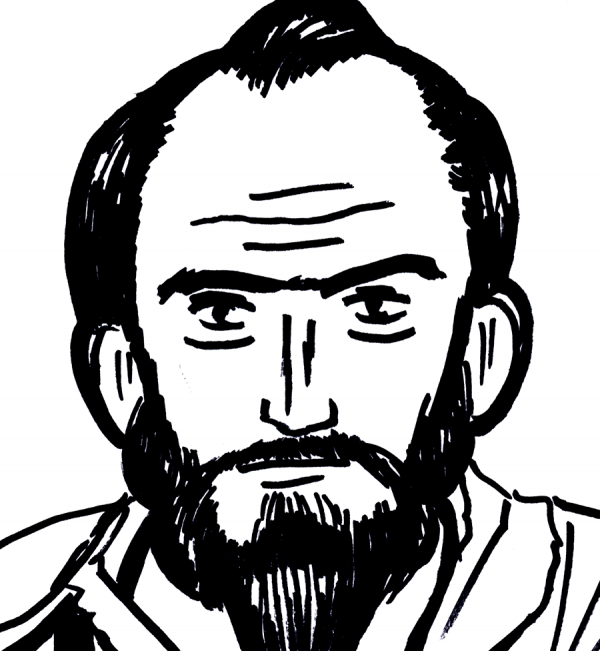

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.